WWII VETERAN LOGGERS, ROCKING CHAIR, AND COMMODITIES: THE 1950’S VERSION OF UNEMPLOYMENT

My Dad was a logger. When he worked, he worked hard, long hours at a dangerous and physically demanding job. In the summer he would work twelve hour days six or seven days a week. By the mid 1950’s logging became even more difficult for these men. Much of the old growth timber had been logged off from low lying locations. The crews now had to drive farther into the mountains to get at good timber. This meant they were logging in higher elevations and on some dangerous, steep terrains. This also meant a shorter logging season as rain and snow would wipe out the crude roads built by caterpillars and steam shovels. These tough men were willing to work in the freezing and miserable conditions, but it was impossible to get the logging trucks out to the mills using those makeshift roads. The working season for loggers was reduced to about eight months; from mid- March to mid-November.

During the winter months the out or work loggers would receive financial help from the federal government through a program called Unemployment Compensation. Loggers and other seasonal workers called it “Going on the rocking chair.” Each Tuesday, Dad and three or four of his “logging in the kitchen” buddies would share a ride to Chehalis to pick up their check. “Logging in the kitchen,” means those times (quite often in the winter) when Dad’s buddies would gather in our kitchen, sit on the counter tops, drink Oly and Rainer and tell logging and WWII stories. I loved sneaking in to my Gramma’s room, which was next to the kitchen, and listen to those stories. If only I had a tape recorder.

Two of his unemployed friends who always went along, were Orville and Wilson. I am not using last names as these were real people. They were really nice guys and had their peculiar quirks.

Orville was a slow talking transplant from the Appalachian Mountain region. He brought his family to Washington so he could get out of the coal mines and work “outside in the elements” as he would say. He was short and stocky with a rather large pot gut or “my beer belly” as Orville called it as he patted the watermelon protrusion half hidden under his shirt. What I remember most about Orville was that he always wore a very tight white tank top t-shirt that had coffee and chewing tobacco stains on the front. Dad said he thought Orville must have found a store to buy them pre stained. He always had a three day old dark stubble on his face and he was almost bald, except for the one inch ring of brownish grey hair around the sides of his head along with a wispy comb over. With his coffee and tobacco stained t-shirt ending just above the naval, red suspenders holding up his cut off baggy blue jeans, and the ever present Olympia beer in his hand along with a Camel cigarette wagging up and down in his mouth as he talked, Orville was quite the site. By the way, loggers cut the off the hem of their jeans so if they would rip away easily if caught on a branch or drag line. Clean work jean were suitable “going in or out town attire.”

Orville looked like a weird couch potato, which is what he was when not working. However, when he was on the job he was one of the best cat skinners around. A cat skinner is the guy who operated a caterpillar, the large tank looking machine with a blade on the front used primarily for building roads. Orville was a cat skinner before the war, but he honed his skills even more building roads and airport runways for the Seabees on various islands in the Pacific. He and his crew would come ashore with their equipment even as fighting still raged nearby and begin building needed runways. This was non heroic, but important and dangerous work that helped win the war. After the war, his road building ability was always in need by the various logging outfits in the area. He would be hired to build a road, spend a few days getting the job done, get paid and then go back to his couch to drink Oly and watch Wagon Train or Gunsmoke.

![C:\Users\Hasletts\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Windows\INetCache\IE\AYCROD4Y\220px-ACB_2-_Beirut[1].jpg](http://salkumreds.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/c-users-hasletts-appdata-local-microsoft-windows-1-2.jpeg)

![C:\Users\Hasletts\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Windows\INetCache\IE\AYCROD4Y\6893268581_289ab1fd96_z[1].jpg](http://salkumreds.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/c-users-hasletts-appdata-local-microsoft-windows-1-3.jpeg)

Seabees at work and a couple of pictures of CATS.

Dad’s other friend, Wilson, was a WWII veteran who was near deaf from being in command of one of those large guns on the battle ships. Dad would make him mad by purposely saying something softly so Bob would have to say “huh” several times, before he realized that Dad was setting him up. He would then yell something along the lines of “don’t make fun of a deaf vet you son of a bitch.” Dad would laugh and within an hour do it again….and Wilson would fall for it again. I am not sure if Wilson was Wilson’s first name or last. Everyone called him Wilson, like the volleyball in Castaway I suppose. Wilson did strange things like sleep with an alarm clock under a washtub on the end of his bed so he would make sure to wake up in the early morning for work. He was a pretty big man, at least to me, and it was funny when he started to tell a story because he had a high pitched voice like Gomer Pyle.

My Dad’s favorite Wilson story was about eating lunch out in the woods. Each day the loggers would break for lunch and bring out their black metal lunch pails and large thermoses. One week, beginning on Monday, Wilson opened his lunch box and muttered, “God Damn it. Peanut butter again.” He did the same thing on Tuesday and Wednesday. On Thursday, he opened his lunch box, grabbed his sandwich, yelled, in his best high pitched Gomer voice, “God Dammit! Not peanut butter again!” He stood up and threw the sandwich in a nearby creek. Dad finally said, Wilson, why don’t you just have your wife make you something else.” Wilson, replied, Oh, I make my own lunch.” That was Wilson; the Yogi Berra of Lewis County loggers.

Sometimes there was a fourth person from the “kitchen loggers” that went along. He wasn’t with the group long, before moving, but he was a guy everyone remembered. Marlon was tall and thin with a slight chin and long nose. He was clean shaven and always wore clean and pressed loggers’ signature clothes – striped hickory shirt with cut off ragged sleeves, cut off baggy jeans, wool socks and Romeos. He was not one to tell stories, but laughed and enjoyed those that others told. There was a quiet, confident reserve to the man. He was well liked and actually revered for a very good reason. Marlon had won the Congressional Medal of Honor in WWII. I never did know why or how at the time, because he, nor anyone else, ever told that war story. I googled it for this story and I learned his unit was pinned down and about out of ammo. He rushed the enemy pretty much like you would see in the movies and single handedly, killed between 16 and 20 Japanese at close quarters, firing off so many rounds his left hand was badly burned from the heat of his rifle firing so fast and often. He went back to get wrapped up and led a group of volunteers to finish the job. The citation noted that his action saved over a dozen of his fellow soldier’s lives.

Even among WWII veterans who had seen plenty of action, this put Marlon on a higher level.

I went in to detail about Orville, Wilson and Marlon because they are typical of the Greatest Generation, as Tom Brokaw so aptly named them. In the 1950’s we kids were surrounded by WWII veterans, who came home to go about their lives. There was the postmaster who was shot out of his plane and spent months in a German prison camp, a barber who was a recipient of several medals or a teacher who had two purple hearts, and so many more. We just saws them as our little league coach, scout master, or Sunday school teacher.

What about the ring leader of this interesting group; my Dad? He was a veteran too….sort of. On Monday, December 8, 1941, my Dad and his brother, my Uncle Marshall, stood in a line that ran around a city block in downtown Seattle, to enlist in the service. Dad, being almost 30 years old and having three kids, was turned down. He continued to apply each month for the next three years, while working 7/12s (twelve hours a day, seven days a week) as a welder in the Seattle shipyards. Each time he was leaving to drive to the enlistment office, Mom would beg him to stay home. After the hardships of the Depression, she was finally living in a nice house and Dad was making lots of money. She did not want Dad going off to war and possibly not coming back, leaving her with three small kids. But, Dad was determined to be part of the war effort.

In the spring of 1945, the war in Europe was winding down, but estimates by the War Department was that it was going to take at least 500,000 more men to invade the Japan mainland. Dad was accepted into the Navy in late April, 1945 and was sent to San Diego for training. Germany surrendered while he was in training. He got out of training in August, the week the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. He was mustered out a few weeks later. His entire military career consisted of basic training. He always joked that he was the military’s secret weapon. He enlisted and Germany surrendered. Then he got out of basic training and Japan surrendered. “Hitler and Hirohito knew I was coming” he would say. I know he was happy about finally getting into the service to show he was willing to sacrifice for his country, but he was always a little sad and embarrassed that he did not actually see action as so many of his friends had.

The four WWII veteran loggers would leave about noon for the hour long drive to the unemployment agency in Chehalis, along with a list of items they were to buy at the stores “out town.” It took at least an hour in those days because this was before the Eisenhower freeway system was complete and there was no I-5. Travelers had to drive 10 miles on highway 12 and then another 12 miles on highway 99 (now called the Jackson Highway) to reach Chehalis. Both two lane roads ran through small towns and farm land with free range cows, kids on bicycles, a few chickens, lots of dogs and usually a couple of places where kids had set up baseball fields on the road. Driving was slow.

We called Chehalis and Centralia “out town.” We lived “down under the hill” in Salkum; our house being toward the end of a road down a short hill, that at one time ended up at the old mill site on Mill Creek. When we walked, rode our bike or drove a car the half mile up the hill and along Mill Row to get to the main street of Salkum, we called this “going uptown.” When I write “main street of Salkum” I am referring to Talbot’s and De Grosse’s stores, the White Spot and Goldies café’s, the White Spot Tavern (locals called it Stankey’s), the 76 Station or the 7 unit White Spot Motel. That was pretty much all of the business section of Salkum that I can remember. When we were going to Mossyrock, which was about 12 miles east on Highway 12 and where we went to school, we called this going “in town.” When we were going to take the longer trip to Chehalis or Centralia (two towns close enough to be one if not for history and politics), we called this going “out town”. Going “out town” was a big event for us kids. Centralia and Chehalis had several stores, a JC Pennies, a hotel with 5 stories, a movie theater, a Grey Hound bus depot and stop lights. These were metropolises!

Even today, East Enders (those from Salkum and east on highway 12 in Lewis County) refer to Mossryock as “in town” and Chehalis and Centralia as “out town.” Only those few of us who lived “down under the hill” could use the phrase “up town.”

After the drive ended at the unemployment office in Chehalis, the men would pile out of the car and head inside to be “interviewed”. An employment specialist would ask them a series of questions about their job skills and availability to work. They were asked if they could do such jobs as gas station attendant, carpet layer, grocery clerk, short order cook or mechanic. Of course, these men could easily handle most of those jobs, but no way were these tough old WWII veteran loggers going to take them. They would just say no they were not qualified for such jobs and the “specialist” who knew most of the men personally, rubber stamped the form which said, “no employment available for which applicant is qualified” and gave them their checks. The other reason the men did not take those jobs was because they could make more money by cutting cedar shakes, picking fern or doing welding and get paid in cash.

Dad’s check was for $47.18. For some reason I remember this. I think it is because he never arrived home with $47.18. When Mom demanded to know where the full $47.18 was, Dad had to do some fast talking. This scenario was re-enacted each Tuesday evening or Wednesday morning, depending on how late Dad got home. So $47.18 is instilled in my mind.

Why did Dad come home with less than $47.18? I imagine you have guessed that already. Once Dad and his buddies received their checks, they went to the stores on their lists to pick up items to take back home. These stops would include JC Pennies, Ben Franklin, the grocery, and the drug store. Mom expected receipts from these purchases. When those mandatory stops were done, the men had two more places to go. They first went to the government warehouse where they picked up commodities or as some called it, government surplus. There were various items that were given to people who were out of work and had yearly incomes of….I don’t know, but not very much. The commodities I most remember were cheese, mystery meat, peanut butter and powered milk. More on those choice items will come later in this story.

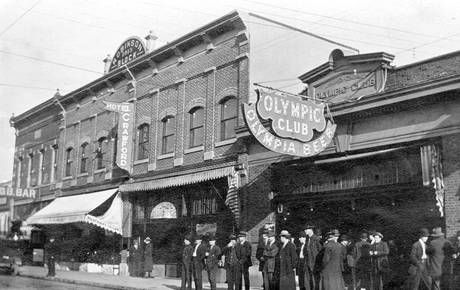

Dad and his buds would then drive the four miles to Centralia to play snooker at the Olympic Club. This “mens’ establishment had been legally around since the end of Prohibition and was probably serving alcohol illegally as a speakeasy during the 20’s. Even in the 50’s women were unwelcome in the snooker area. The managers of the Oly Club, being no dummies, gladly cashed the unemployment checks. Dad would play a few games, drink a few beers, tell a few stories and arrive home with somewhat less than $47.18, which Mom would quickly grab and count. Most days, or early evenings, the amount was still in the $40’s, which was good. Anything below that and lots of yelling would ensue. On the good days there was no yelling and Dad would give me these cool umbrellas and swords. I always wondered how he had time to stop at the five and dime to get me a toy or two or three. When I would mention that to my brothers, they would just roll their eyes and shake their head in wonderment at just how dumb I was.

As an addendum to the above; the Oly Club is now a rather famous tourist destination owned by McMenamins Breweries. It has a movie theater, a few rooms upstairs for tourists to stay overnight, and a restaurant. It still has the snooker room (women are now encouraged to play) and the large black potbelly stove that has been there for about a century. It also is the home to the largest porcelain urinal in all of the northwest. The urinal itself could be a tourist attraction.

These six foot high, five foot wide urinals have to be among the largest in Washington. The bottom is always filled with ice. The Oly Club in what looks like the 1930’s. The pot belly stove which still works and has been a customer draw on cold Centralia days for almost a century.

Even if Dad did get in trouble by not bringing home $47.19 each Tuesday, he made up for it (somewhat) by his stellar work with the commodities. Commodities were various foods that the Federal Government purchased in bulk from farmers and meat packers who had a surplus. These foods would be cheaply packaged and delivered all over the country to government owned warehouses. Low income people could receive commodities once a week. The items would differ each week. Over the years I saw such things as meats, flour, sugar, beans, powdered milk and eggs, peanut butter, and cheese. There are four that I most remember.

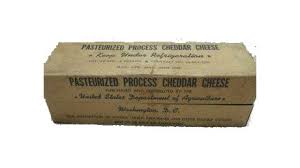

Number one on my list is government cheese. There is even a band called Government Cheese that was fairly famous in the 80’s. This government cheese was very good. It came in two kinds – a hard cheddar and soft, Velveeta like. Both kinds were in two pound rectangular boxes, which made it the perfect size to unwrap, slice off a hunk and build a sandwich or just eat.

I loved them both. The cheddar was so good that those who received the cheese ( as mentioned, you had to be in a low income group) could sell it to those with money, who loved it as well. This, I would assume, was not legal, but it was a perfect combination of socialism/capitalism. We never sold our cheese. We all loved it and fought over who got to eat it. I especially liked the Velveeta soft cheese. My wife, Sally, buys Velveeta now to make dips or tacos. When she sees me sneak a chunk just to eat, she just rolls her eyes and remembers my family history.

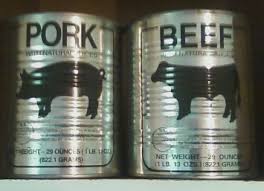

Number two on my list was the mystery meat. Actually this meat, probably made from all the meat scraps from a packing plant, looked a lot like Spam once Dad was finished preparing it. The meat came in a two gallon sized silver tin can with “USDA INSPECTED MEAT” stamped on it. I am not sure who actually would inspect it, but it must have been an entry level job. Dad would take his hand held can opener and cut around both ends and then pull off the top and bottom lid and place the can on a large cookie sheet. He would slowly lift and pull the can off the meat until it plopped onto the cookie sheet. The cylinder of meat, if you could call it actual meat at that time, was covered in a one inch thick layer of semi clear fat that glistened and jiggled, making the whole thing look like a newborn from a space alien.

Dad would take a knife and carefully, so as not to cut into any of that important meat (I roll my eyes as I type the words “important meat”), and slice off all the fat. He now had a meat cylinder that was still good sized, about 10 inches long and 6 inches in diameter and still weighing at least a pound and a half. Dad would then brine it. Brine means to soak in a salt water solution along with whatever spices one would want to add. I am not sure what Dad added, but the end result was successful. He let the meat soak overnight and then brought it out and cut it in half. One half was to be used for baking for a family dinner and the other half was cut into half inch slices for frying.

I remember frying a one half inch thick piece of mystery meat in a bunch of butter and then adding a piece of government cheese and putting them between two slices of Dad’s homemade bread that had been toasted in the oven then slathered in butter. It was awesome and all made with commodities. It, along with all the other government commodities, is a good reason why so many baby boomers have heart problems. Well, that and secondary smoke, which is a whole other story

Dad was also successful, eventually, with the government peanut butter. The peanut butter came in a similar tin as the meat. I remember the first time Dad brought home peanut butter. It came in a similar two pound silver can as did the meat. Dad opened it and we saw that the top third was made up of thick peanut oil. He poured that out to get to the remains. I do remember him saying that the oil could possibly be used in the old WWII Willy’s Jeep we had out back.

Once the oil was poured out, what was left was a slippery slimy brown gob with the consistency of kids’ model clay that had been left in the sun all day and possibly peed on by my dog, Tippy.

The road to success with government peanut butter was a rocky one for Dad. Being a life-long logger, his idea was to use brute force to make things work. He proceeded to try to soften the gob by mixing it by hand using a wooden spoon. After his arms were tired, he decided to hook up his power drill to solve the problem the logger way. He rammed a two inch wood drill bit (Mom asked him if he had cleaned it and Dad did not reply) into the gob and turned on the drill. The entire gob spun inside the can. For some reason Dad picked up the can/gob and as he was cussing it, the can flew off the gob, past my head, putting a dent in the frig. Dad threw that batch away. Being a smart man, he learned that he needed that oil next time.

The next time came soon and Dad was back at it. He cut off the top of the can and poured out the oil and saved it! He then cut off the bottom cover and used a 2×4 to push out the gooey gob onto a plate. Mom asked Dad if he had cleaned the 2×4 with, again, no answer coming back. He then used his very large and sharp hunting knife to cut the glob into several workable pieces. Mom did not bother to ask if Dad had cleaned the hunting knife. He mixed some peanut oil with each small batch and gently mixed it together to make a smooth peanut butter. After he did this with all the batches (I think there were eight) he gave us each a taste. It was very bland with a slight peanut taste. After all his work, we told him it was delicious.

Triumphant, Dad mixed all eight together and put the whole thing back in one of the cans that still had a bottom cover and sealed the top with waxed paper and a rubber band.

The next morning, I heard a loud, “OH, F…! What the Hell has happened to my $%&%&%& peanut butter!” Seems dad did not know that the oil would separate and go to the top on its own. Dad, evidently did not take chemistry in high school. But, Dad was a pretty good high school baseball catcher who could throw out players going to second without getting out of his crouch. He put that good arm to use on the can of peanut butter and we never saw it again.

Dad realized that he needed something to help him make the stuff taste better, be easier to mix and stay separated. I have no idea if he asked around (lots of Salkum people were getting commodities) or came up with it on his own, but the third time was a success. He repeated his splitting of the batch into eight parts, but then added honey and sugar to each of the eight batches. He then put each batch in a quart jar, filling it only half way. With the added honey and sugar the peanut butter was very good. In the quart jars, the separation still occurred, but it was easy to stir it into peanut butter again. Dad was a commodity peanut butter success. Interestingly, when I was in high school our school lunches included commodity peanut butter with honey and a little sugar added. We all loved it.

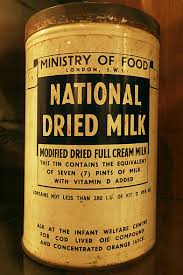

Dad’s only failure was with powdered milk. He would get a big box (think Costco Tide big) of powdered milk each Tuesday. Some of the popular items like flour or cheese we did not get each week. But, somewhere in the United States there was some powdered milk factory with a cushy contract from the federal government because we received this God awful stuff each week without fail. Mom told Dad not to accept it and he was told that if he did not take the powdered milk, he could not have any of the other commodities. Rather than just throwing it away, Dad took on the challenge of making it drinkable.

His first try was to mix it up with water as directed on the box. All of us kids – and Dad – about gagged. We said we would never drink it again. Now Dad was not one to out and out defy. That was not a good idea. I NEVER did it, but I witnessed my two brothers trying it and it was not good. Dad was not abusive, but he would use the switch or a very thin piece of kindling on Rich or Jim when he felt it was needed. He never accepted defiance.

However, when we all (including chicken me) said we refused to drink the milk, he did understand because it gagged him as well. He made us a deal. If he could make the powdered milk taste enough like real milk that when we drank it we did not realize it was powdered, we had to keep drinking it. We agreed. Our regular milk was either whole milk in a glass gallon jug from Alley’s farm or from Talbot’s store in Darigold Dairy half gallon cartons. My brothers, sister and I kept a close eye on those two. Every three days or so Dad would try to some version of powdered milk. I remember ½ powdered with water and ½ whole milk from Alley’s disguised in a gallon milk jug. Upon the first drink we all would yell,” FAKE or POWDERED!” Dad would reply with “shit!” He tried to put one third powdered milk in with two thirds Darigold in the carton. We recognized that upon the first drink. Once he realized we could recognize powdered milk by the residue it left on the sides of the glasses, he even resorted to buying colored plastic glasses. No matter what formula he tried or how he tried to fake us out, we always would yell, POWDERED.” He finally gave up and the powdered milk was used in the compost pile. Funny how something that simple can end up being a great family memory.

I am writing an addendum to this story because I don’t know where else it would go. When winter set in and Dad was out of work, he would go see Mr. Gesche, my principal when I was in grade school, or Mr. Deacon, when I was in high school. He would ask them to make sure I had a lunch card and that no one knew it had not been paid for…yet. The two principals knew Dad was good on his promise to pay for the entire bill when he went back to work in the spring. I am sure I would have been happy to have made my own lunches as I regularly cooked my own breakfast and dinner by the time I was a sophomore. But, for some reason, Dad really wanted me to be like the kids “who had money.” He went to Mrs. Rockwood, who was the “lunch lady” and ask her to do the same. She placed my lunch card in a pocket just like everyone else. He did this for probably 12 years (all my schooling – I did not go to kindergarten). When I became the principal of that same school many years later, Mrs. Rockwood, long retired, but still living in Mossyrock, told me the story. I was blown away. It made me even more determined to help those underprivileged kids.